A radically different approach to clarifying roles in a matrix setup

Over the past decades, we could witness the increase of structural complexity in corporates but also SME’s. The increasing need to integrate different views and underlying needs in management and decision-making processes, such as regions, product or service types, technologies, customer segments’ and so forth, led to complex matrix setups. It provided a structural answer to the rising complexity. Today’s mainstream opinion about matrix setups reminds a bit about democracy: it’s not solving all problems, but by now it is the best option we have come up with. Thus, any kind of (implicit or explicit) matrix structure is meanwhile the dominating setup of today’s organizations in global markets.

But here’s the challenge. Matrix structures did one thing well. They delegated complexity into individuals. Individuals became the intersections where conflicts of interest crystallized. And individuals were the ones that needed to learn to handle this challenge. Learn to accept that successfully acting in a matrix structure needs to build on the assumption that there is not one reality. Rather, there are as many realities as people in the room and thus a joint reality only emerges from dialogue. Many organizations missed out on that competence building. The structural setup was introduced, but the skills to navigate in this new context were most often not trained. But is that surprising? I guess it’s not. Since many organizations follow(ed) the paradigm of organizations as machines, it’s just a logical consequence to think of implementing new structures as a linear process. You analyze, you make a plan, you roll it out. It’s just a matter of communicating well and executing with discipline. Well, is it really?

Meanwhile, the stories of painful experiences with matrix structures have spread and organizations have been searching for ways to handle this issue. Manifold versions of responsibility assignment matrices have been developed to deal with that lack of clarity on who does what, who needs to be involved, informed or consulted; among others the RACI(Q)-Matrices, or the RAPID-framework (all links to Wikipedia). All of them are aimed at clarifying roles and key responsibilities in cross-functional/departmental projects and processes. Yet, they don’t seem to do a great job in capturing organizational reality in a proper manner. For several reasons.

Creating such responsibility assignment matrices takes quite some effort. Once this effort has been taken and clarity on who does what has been created, it’s just human to lean back, feel relieved and proud about the result. And to follow the wish that this was a one-timer to create ultimate clarity and now things should be clear and remain unchanged — ideally forever, but at least for a while. Very rarely have I seen organizations establishing regular checkpoints to review responsibility matrices in a structured manner. They are static. Even though we all acknowledge that organizations operate in dynamic complexity contexts and things change fast.

To be clear: it can be very helpful to map such key responsibilities. Yet, in many cases these matrices don’t meet the threshold of getting concrete enough to integrate different realities/perspectives into common ground. Let’s take an example of a client organization. They had a responsibility matrix mapped out and it stated an “I” for the duty to inform a certain person (role). After a while acting in this setup conflict arose around people that didn’t feel informed well enough, although the person with the responsibility to inform did so. It went on to blaming each other for not sticking to agreed responsibilities and the conflict leaked inappropriately. Only when they made space to have a deeper conversation about their needs, their (implicit) pictures of what “inform” meant for them and the related expectations towards each other, things changed. The higher granularity on what “inform” does mean in this relation allowed the involved parties to find common ground. It was very much about making the implicit explicit. A simple “I” in a table didn’t do the job.

Many examples of such matrices I come across in organizations don’t come with the clarity on how to amend or review them. Neither is clear who can trigger such a process, nor how the decision-making process looks like. Unless specified it only remains with the (higher) superior. In many cases that means that matrices remain unchanged as long as possible. Either until they become irrelevant and people don’t refer to them anymore because they do not reflect their reality. Or until a person with the authority to decide so, is (or most often got) convinced that “now it’s time to review”. That typically needs a pretty high level of felt pain. The option to integrate perspectives on a continuous base by doing minor amendments quickly rather than huge changes once in a while is often not considered.

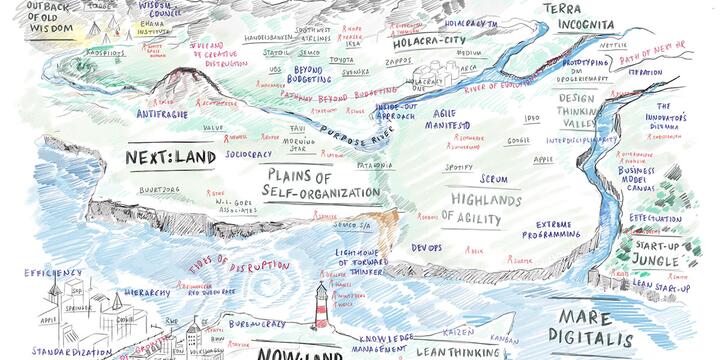

So here is another option. Maybe one more appropriate for rapidly changing environments. An approach that dwarfs and Giants successfully applied in various organizations to create more clarity on matrix interfaces. It builds on the following assumptions:

- Reality emerges from dialogue. Clarifying expectations is a continuous social process. We acknowledge that there are always different perceptions of the same situation.

- The results of such clarification processes will always be imperfect and beta. Agreements need to be fluid and subject to change.

- The process needs to account for learning and evolving. Rather than a one-time-fix we seek for iterations of creating ever-greater clarity. Start by starting, keep evolving.

Our approach

Step 1: Pick your battle :-)

Define which interface or interactions have the highest friction at the moment. That might be lack of clarity on who does what precisely, what can be expected of whom, who can decide what and so on. Identify the roles involved in these interfaces.

Step 2: Capture your individual reality

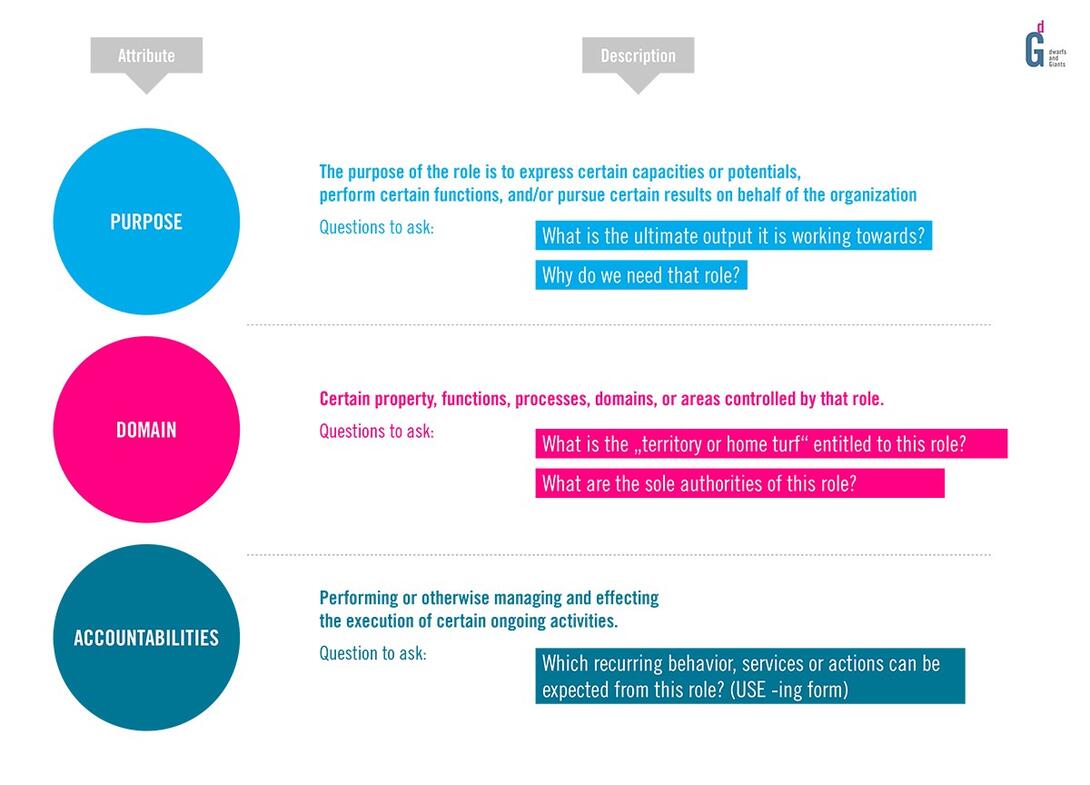

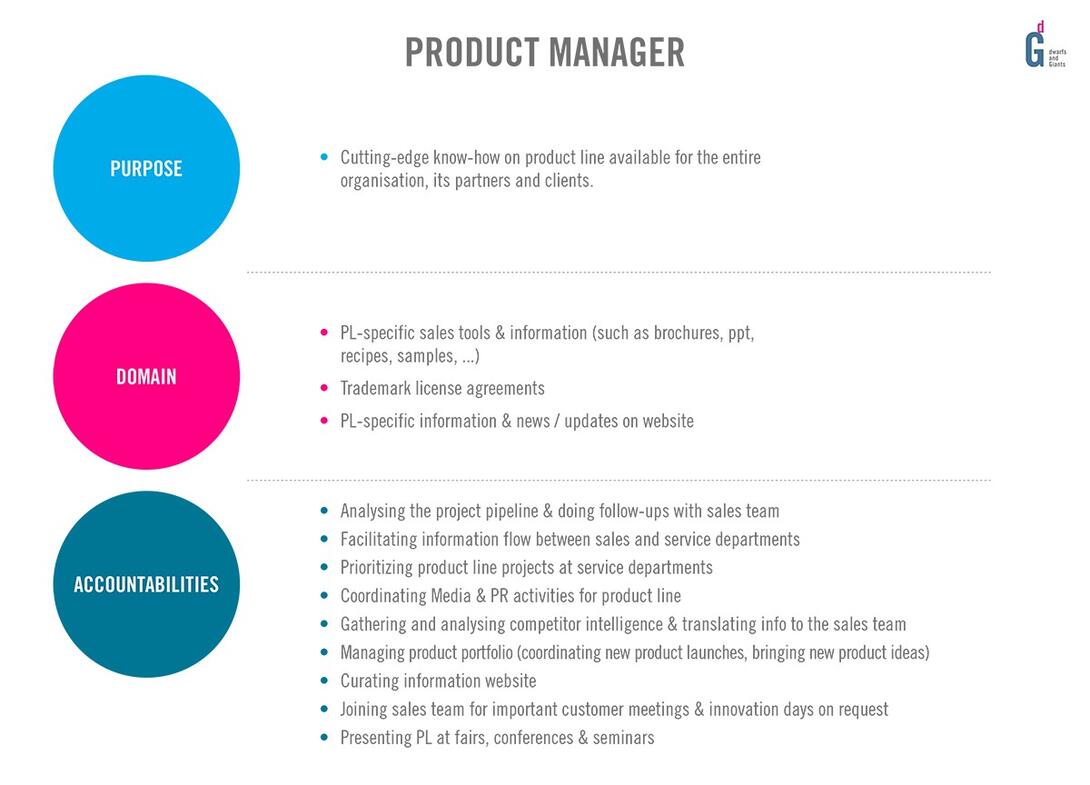

To get started we use the role description template of Holacracy – an operating model that is designed to distribute authority across the organization. Holacracy describes roles with three essential elements (apart from the role name): 1) the role’s purpose, 2) its domains and 3) its accountabilities.

We send the template to all people who fill roles that need clarification. Typically based on some more guidance they fill this template upfront to capture their view on existing reality individually. We ask them to just capture what is and not what could or should be. Typically, we receive first drafts and provide feedback, ask for more clarity or preciseness to arrive at a minimum viable role description before entering the next step.

Step 3: Processing roles via consent decision-making

After this preparatory process, we gather all involved roles in a workshop. The first step is to establish a social container that feels “safe” for people. The importance of this step is often underestimated. Apart from this social dimension, it is very important to frame, that it’s not about creating ultimate clarity, but a next step towards more clarity that can be revisited any time. This typically relieves pressure. Most important however, is the decision-making process that is used to arrive at agreed role definitions. It should provide and hold the space to integrate (even opposing) perspectives without getting stuck in relational dynamics or tensions. In our workshops, we made the best experiences with consent-based decision-making. We mainly used the integrative decision-making process of Holacracy and tweaked it a little bit with regards to different ways of testing and integrating objections, to increase fit with the context we were in. The general process looks like this Integrated Decision Making process of the Holacracy Governance. This is how a possible result of such a process looks like:

Step 4: Agree on the evolutionary process to keep the roles close-to-reality

The last step in such a workshop is to map out the process of keeping the roles “transparent”, “lively” and “relevant”. This includes answering questions such as:

- How are the roles published and where? Which software can we use to support the visualization and accessibility of our role-setup? (Hint: If the answer looks something like: “a document filed somewhere on sharepoint” then you should probably reconsider :-).

- What’s an appropriate sequence to revisit the roles based on experiences/feedback from reality?

- Which roles are accountable for setting up this process, scheduling and facilitating these review workshops?

- How do we deal with more urgent needs for clarification?

- What are our guiding principles (or rules of engagement) when acting with this new role setup? (e.g. Act entrepreneurial: if not clarified, just do it, don’t ask AND create more clarity once we meet again)

- How do we hold each other accountable?

What we’ve learned so far

So here is what we learned about the benefits of such a process:

Such role definitions — in their simplest form — are a (consistent) bundle of expectations. Accountabilities make explicit what can be expected on an ongoing basis from a person that fills that role. Thereby they structure the interactions between people filling different roles: the role-ations. This is reached via a process of aligning these expectations without outvoting different opinions but integrating them in a very efficient manner. The process provides space for being heared and being taken equally serious. There is no perspective that is more relevant or more true than any other one. This is deeply appreciative towards the people involved. Joint reality (or common ground) emerges from dialogue.

The approach includes an agreed process how to amend the roles. It allows or even encourages to adapt any time. More precise: any time you have more data about what’s still unclear and needs further clarification or amendment. Thus, this approach supports the organization in adapting to changing environments and needs. It helps to create a learning organization.

Many organizations follow the temptation to invent clarity in mind (predict and control). Clarify as much as possible upfront to prevent conflict or other tensions. We often tend to design tension-prevention systems. In rapidly changing environments it seems much smarter to build organizational capacities (e.g. skills, structures and processes) that support rapid learning and processing tensions when they occur. Let reality guide your way: tension processing over tension prevention.

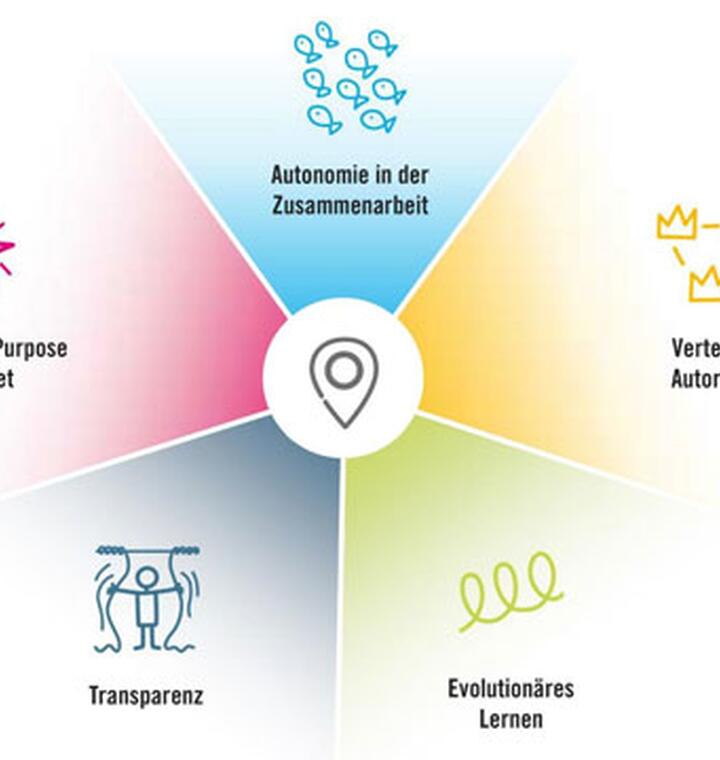

Clarity in roles very much supports two of the fundamental building blocks of next:land organizations outlined in our manifesto: distributed authority and autonomy in collaboration. The more explicit expectations towards each other are, the safer the space to act. I can trust, that’s what we agreed is the currently “valid” point of reference and common ground for our interactions. And we will find solutions as we move ahead, as soon as tensions arise.

So relax, nothing’s under control.

This article was originally published by Gerald Mitterer on Medium on October 10, 2018.