Dynamic Strategizing: About Agile Forms of Strategy Work

Nowadays organizations operate in a world in which disruption paradoxically is almost considered a normality, in which technological, digital, societal, and political changes compete in such a dynamic race with complex business model innovations that nobody is able to predict today who will be among the winners and losers tomorrow.

We believe that organizations cannot master the challenges of a VUCA world within their old boundaries and habits, and that the tensions created by the changing conditions will only intensify when the old formulas for success from the last century are applied.

Even traditional forms of strategy work reach their limits in this context. The value of analysis-based long-term projections, scenarios of market development, and long- and medium-term planning is diminishing steadily. The historically grown division between mental and manual labor, where a few people at the top come up with what many others at the bottom are supposed to do—by means of specification and control—makes most of the strategy processes fail.

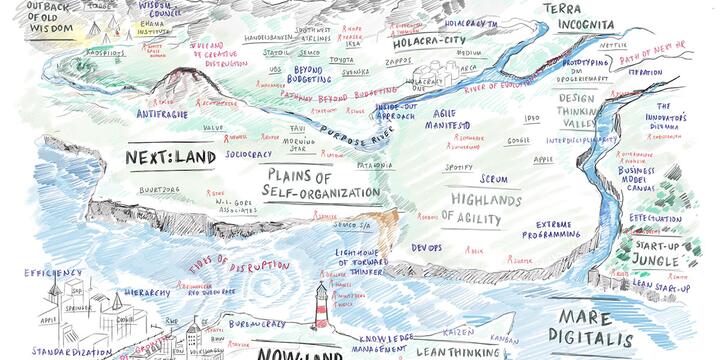

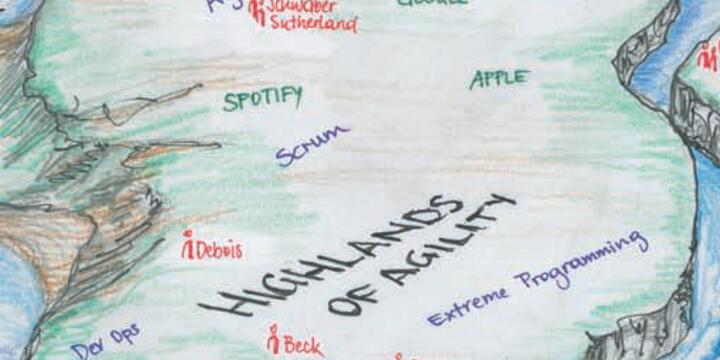

When it comes to the question, in which direction organizations need to develop in future, no other citation cuts right to the chase of the matter than the one by Steve Denning quoted above. More and more organizations these days set out on this new path for more agility—a new way of working, characterized by self-organization, distributed authority and flexible approaches as well as the development of Cultures of Innovations. It’s the path into the next:land of organizing, as we at dwarfs and Giants call it. It’s a land where completely different principles of alignment of organizations apply (learn more about the five principles of self-organization and the shift from now:land to next:land from our Manifesto).

But how can organizations increase their strategic adaptability and speed of change in a world of rapidly and permanently changing environments? And which kind of strategy work do they need to do that? We believe that the future of strategy work in organizations needs to be rewritten entirely.

If everyone has to think outside the box, maybe it is the box that needs fixing.

Malcolm Gladwell

Mount Strategy – Strategy Work in now:land

Imagine you’re standing on top of a huge mountain that surmounts all other elevations in the old continent—Mount Strategy—during a board meeting of an international industrial company in now:land. The decision papers of a strategic document that was developed by a small group of people under the direction of the administrative department ‘Corporate Development & Strategy’ are on the table—exciting analyses of trends and business areas, supported by SWOT and a portfolio analysis. The proposal for the company’s strategic alignment for the years to come is summarized on nearly 100 PowerPoint slides. All decision-makers at the table agree on that. On the one hand, the room is filled with a bit of pride. After all, it took them almost a whole year of intensive work, not to mention the high consulting fees and the numerous votes that had been necessary. On the other hand, a certain hesitation in implementing the proposal can be felt because a resolute decision for this strategy would exclude many others and thus turn out to be risky. A slight uncertainty remains if all things had been taken into account leading to the development of the ‘right’ strategy. And: despite all determination and euphoria, it still has to be decided on how to implement the strategy.

In 1980, Michael Porter laid the groundwork for the prevailing understanding of strategy work on Mount Strategy, which from that time on characterized corporate development in now:land—handpicked delegates, beginning with comprehensive analyses of trends and markets, etc., but without saying how to implement the results. The strategy on the table, though, has to reach about 6,000 employees around Mount Strategy and serve as a guiding basis for their daily priorities, on all hierarchical levels and in all business units spread over the entire continent. And it should be done quickly and precisely so that the allocation of the resources of all executives and employees would become effective in all business sectors. Only this can measure success.

And yet, numerous studies by renowned researchers have shown in recent years that this is exactly where the vast majority of cases fails to succeed. More than 90% of strategies in now:land fail in the implementation.

What are the reasons for that failure? Even if it were accepted that strategy work on top of Mount Strategy was aimed with top priority at the organization’s sustainable development—and not at short-term maximization of revenues, EBITs or other figures that make a positive impact on executive bonuses or the renewal of three-year management contracts—a hundred-year-old assumptions take effect that had been successfully applied in contexts of growth but do no function anymore in a VUCA world.

- The first misjudgment is the period of time that a strategy developed at the top needs to become effective at the foot of the mountain. In large organizations it is not uncommon that strategies are one or two years old until they reach the base. Most of the parameters of the time of its creation have already changed radically during that period so that a change of direction becomes necessary again.

- The second misjudgment is the operationalizability of global strategies developed on top of the mountain, far away from any complex corporate reality. What theoretically is supposed to add up to a big picture in the strategy paper in terms of increasingly detailed specifications and single targets simultaneously and globally on all markets, locations, and supply chains, is prone to fail because of too many interfaces in a complex and interconnected corporate reality.

- The third misjudgment lies in the willingness of the employees to align themselves with the strategy coming from above. In practice, however, the attempt to formulate meaningful and action-oriented guidelines often fails. Top-down strategies offer little space for people to make sense and interrelate with them. Instead of individual sensemaking, a few people try to provide meaning for many people. The long-term ‘emptying of meaning’ and the ensuing negative effects on intrinsic motivation have already been widely studied and discussed.

- The fourth misjudgment is the belief that a few decision-makers at the top are able to make all important decisions. It’s exactly this assumption, originating in the 20th-century management practice—the division between mental and manual labor—that has no basis anymore for the dynamic complexity of the 21st century. The information that needs to be processed today is too manifold and comprehensive, and the decision-making procedures take too long when the need for a decision and the decision-making authority are uncoupled.

Hills of Strategizing – Agile Strategy Work in next:land

The Strategizing Hills are a wide and open hilly landscape in next:land, in which a lot of different people are moving around in order to continuously reflect on the organization’s strategic alignment and to keep it competitive in constantly changing contextual conditions. Like a large number of sensors, people are looking for new ways and climb new hills. They’re trying to find new developments behind every elevation, new contexts, surprises, and opportunities which are then included as new information into the current dialogue. Guided by a common understanding of the company’s purpose as well as clear decision rules, decisions are permanently and quickly made. Are we going into the right direction? What is there to do for us? Where shall we send more people, where invest more resources? Where do we want to meet next to exchange views, to give feedback, and to learn from each other?

We are now in next:land at an international, medium-sized company with almost 1500 employees. 30 people are gathered together in a large office and write on Post-its. There are circles of chairs, flipcharts, craft things, colored papers, and a bunch of pencils. People from various departments and business units are working together in interdisciplinary groups of five, engaged in a Design Thinking process. Right now, one group is analyzing customer personas—a work package from the backlog of their Agile strategizing projects. The goal of the ten strategy initiatives is to lead the company into a new market and develop suitable business models in dialogue with a lot of internal and external stakeholders, using different points of view in form of Agile projects—knowing that some of these projects can be stopped any time when feedback from reality signalizes that they don’t make sense anymore. This process is not instructed by superior managers but guided by the question: How can we best manifest the company’s purpose in the world? The goal of these efforts is not a final strategy paper but an ongoing dialogue about strategic preferences, concrete ideas, and palpable prototypes. From this process, a constant flux of new impulses and ideas is entering the strategy backlog—ideas that are taken up by the teams and processed in a Sprint-logic. What promises success and triggers a positive response will be enhanced and refined. Reflecting, implementing, and involving customers are not separate processes but one continuous evolutionary process, in which a number of different perceptions are included. Welcome to the Hills of Strategizing.

The American organizational theorist Karl E. Weick, one of the earliest pioneers of next:land, was one of the first thinkers to abandon the idea of static organizations in favor of “organization as a process.” A revolutionary idea transforming now:land static top-down strategies into a dynamic process of strategizing in next:land. Continuous strategy work as an ongoing dialogue that involves as many people as possible from the entire company context. Instead of contemplating strategies high up on a lonesome peak, here the attitude prevails that strategic options for action should regularly be tested.

Strategizing breaks the patterns of common strategy work consciously. There are no conventional analyses producing high stacks of paper as a result anymore. Instead, different players in the company exchange views and constantly produce a mutual picture of the status quo and develop strategies for the future. Strategizing replaces the separation between development and implementation by an ongoing dialogue about strategic opportunities and guiding preferences for everyday business, knowing that preferences in a VUCA world are a) changing permanently and b) can never be one hundred percent clear. For the world is a complex and dynamic thing, the future not predictable. In strategizing there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ path into the future. There are only paths into the future.

The result of all movements in the Strategizing Hills is a vivid and evolutionary strategy that develops step by step and is enriched by constant customer and employee feedback—a strategy that is created while walking. In the next:land Hills of Strategizing, it’s not the one and only strategy that is decisive but the speed of learning.

Today the most important strategic question for any organization is this: Are we changing as fast as the world around us?

Gary Hamel

The Path into the Hills of Strategizing

Forget strategy as a paper. Create an always-on strategizing-practice.

dwarfs and Giants

In our consulting work, we at dwarfs and Giants are reluctant to reveal too many steps and details of the transition from Mount Strategy into the next:land Hills of Strategizing in real transformation processes in order not to fall into the trap of linear prediction and control (Predict and Control Mode).

Instead, we develop a concrete and individual process in co-creation with every organization that step by step will lead into the next:land of organizing. The starting point of each company is as unique as its identity and history. And every company has to find its own path into the next:land of organizing. Nevertheless, there are core elements of the strategizing process which can be revealed.

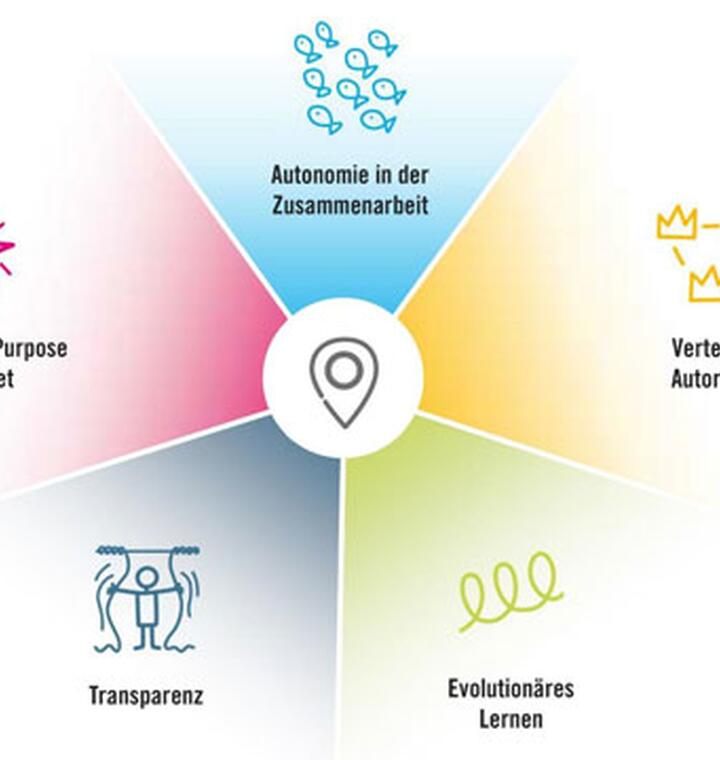

Every individual step that organizations take on their way—accompanied by us—is guided by the five basic principles of organizing in next:land. They are fundamentally different from the principles in now:land. They act as a magnetic field in the whole of next:land and serve as a point of alignment for organizations in their development and on their way into the Strategizing Hills. At the same time and from the very beginning we thus practice the ability of the organization and its employees to deal with insecurity. What does it mean to ‘run on sight’ and orient oneself by the nearest visible point without losing direction? What does it mean to have one’s decisions oriented toward the next possible step instead of some final, perfect solution?

4 Elements for the Development of a Strategizing Process

Bringing people together—shaping and hosting processes.

The inner purpose of an organization becomes the guiding star and reference point in a dynamic environment. Takeuchi’s “purpose is at the essence why firms exist” puts it in a nutshell.

Perceive resource allocation as a central filter and stimulate a permanent strategic dialogue about guiding priorities!

Responsiveness and learning as core elements of understanding.

Find out more about the 4 Elements of Dynamic Strategizing in our whitepaper (Download below):